Life Writing

Sara McManus

School of Education, University of Northern British Columbia

EDUC 446: Aboriginal and Indigenous Education: Epistemology

Karine Veldhoen

December 6, 2022

I naively felt prepared to enter a new career as an uncertified TTOC. My biggest responsibility was keeping the class safe. Learning was a bonus. That strategy didn’t work when I was called into McNaughton Centre. I was in way over my head. I was teaching Foods, but I hated cooking; I had zero recollection of anything related to trigonometry; and I lived a privileged life with no training or background in supporting the students within an alternate school.

I found myself learning with them and making connections to build relationships. I didn’t enforce the strict rules the other teachers did. So, of course, they had fun at the start, but I slowly earned their collective trust and respect. I was teaching on pure instinct, and somehow, I became the space where students could be themselves, and in return, they were ready to learn.

In my second year, I taught PE and Leadership instead of Foods and offered them the freedom of choice in their learning. Every six weeks, when our cycles changed, my students would look at the curriculum with me, and they were given the responsibility to choose what they wanted to learn about.

Now you’re probably wondering – how does this tie into my Grade 2-3 practicum? Well, here it is. The spring before we started the B.Ed program, my leadership class chose mental health for their six-week cycle. They wanted to plan an event for the whole school, a fun day. They named it, “Honour Your Mental Health.” They worked extremely hard planning and to start the day off with the right energy; we invited Hollie from the Ab Ed department to teach everyone how to smudge properly.

We hosted a waffle breakfast, and then all 45 students sat in a large circle as Hollie came in with her drum and sang for us. She passed a smudge bowl of juniper from student to student around the gymnasium as she talked about smudging and the four sacred medicines.

Unexpectedly, one of my leadership students who had planned the event left the room, clearly upset by something. Now, I could have written a life writing just about this student and all the things they taught me in the two years we shared, but I don’t have the time. I’ll just give you a fake name, Sam. Truth be told, two years ago, I could have only pronounced the English part of their hyphenated last name anyways. Their mother’s Russian Doukhobor family raised Sam in the Kootenays, and they only had minimal connection to their biological Inuit father.

Later in the afternoon, I asked Sam why they had left. They were furious. They were filled with questions like: Why do we always have to focus only on Lhtako Dene and Carrier traditions and cultures? Why can’t we learn about other Indigenous cultures? They poured their heart out about being Inuit and being forced to learn about other people, but not their own. In the Doukhobor community, as a young girl, they had learned all about the traditions and cultures of her mother’s people, but they knew nothing of their father’s side. The Quesnel schools were filled with Dakelh and Carrier words, games, and food. Sam explained that even though they were part of the planning, they were suffocated by the burning juniper. They felt genuine anger towards the school and me for forcing a ceremony upon them. There was nothing that I could do or say. I had no answers.

That summer, I photocopied every Inuit story from my Indigenous Literature course just for them. I left it with their English teacher as I embarked on my educational journey to where I am now. Many of you may have heard me repeatedly question why we are so focused on local epistemologies in our classrooms, and now you know why. My teaching is driven by creating relationships, but I didn’t realize how interconnected my teaching was to the Circle of Courage. I worked hard to ensure that every student knew they belonged, which led us to a space where mastery, independence, and generosity could be achieved. But for Sam, my time had run out, and it has bothered me ever since. I wonder, how long did that sense of not belonging fester inside them before they could articulate how they felt to me?

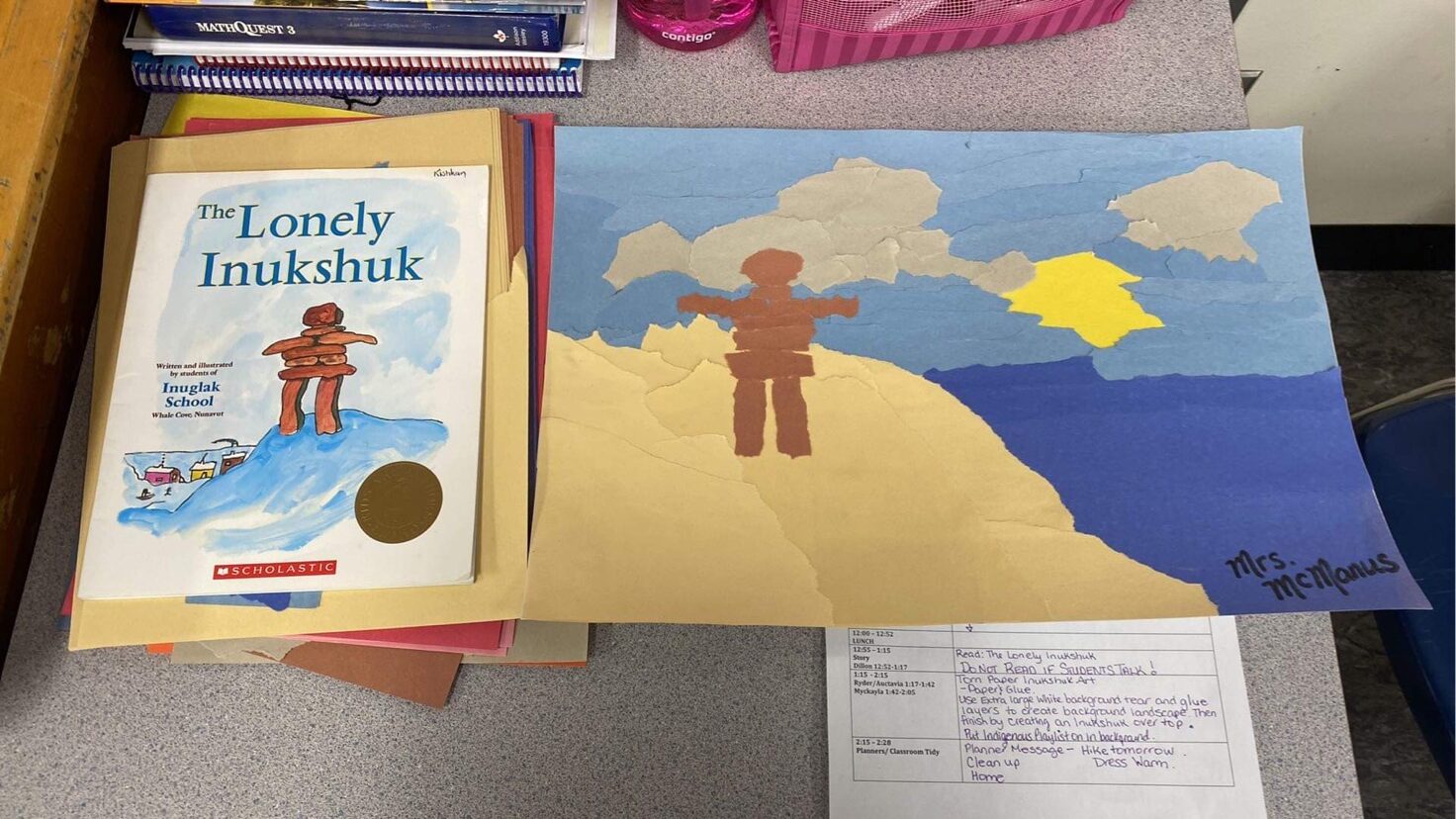

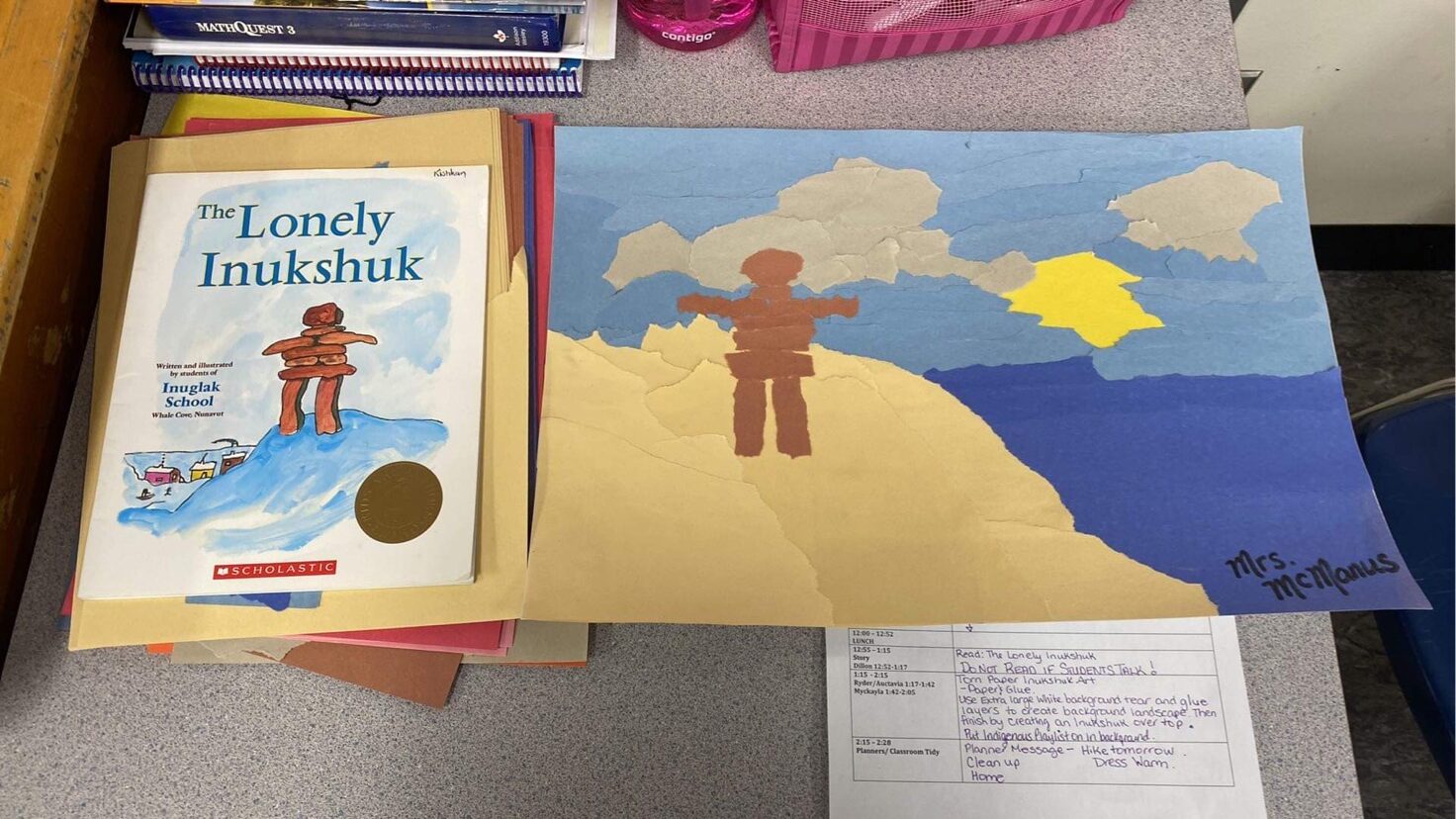

In my practicum this semester, we contemplated what I should do for some of my afternoon blocks. My classroom teacher pointed out several great books to read aloud, which lent themselves easily to art activities. As the days passed, I was drawn back to one of the books she suggested. I read the story and created an exemplar of the art for the students to follow. When I went home that night, I sent Sam this photo on Snapchat:

There was no need for me to caption it. They knew exactly what I had done. I received an immediate: Thank you. We chatted for a long time that night, catching up on what they had done since graduation last spring.

The next day, when I introduced the book, I told the students why I chose the story of The Lonely Inukshuk. I explained why I thought sharing stories from different Indigenous peoples was important. The gift I received from those grade 2 & 3 students was in their response. “I’m part Cree,” said one boy. “I’m Metis,” said another. “I don’t know what I am, but I’m Indigenous!” exclaimed the boy bouncing at my feet. In a school named for the traditional lands that it is built on, only one out of the six self-identified Indigenous students is from the Lhtako Dene First Nation.

They loved the story, and it affirmed a new pedagogical way of thinking within me: I feel empowered to move forward in creating classrooms where I am not teaching Indigenous epistemologies like a foreign culture but instead able to fully integrate it for what it truly is – a mosaic of First People’s cultures which exist nowhere else on earth. Meaning that I will always honour the land, traditions, and cultures of the First Peoples where I teach, but in doing so, I will also be cognizant of the needs of the individual learners in my classrooms to ensure that every one of them sees themselves reflected in their educational journey with me. My Lonely Inukshuk lesson honoured my student whose last name I can now pronounce.